The Nameless Dead of Wetterfeld - The Bloody Spring of 1945 in Bavaria

"Remember the dead in prayer". This is the final phrase on one of the memorial stones that Rodinger Mayor Franz Reichold and the Catholic town priest Holger Kruschina consecrated in early September 2015 in the Gemeindehölzl of Wetterfeld.

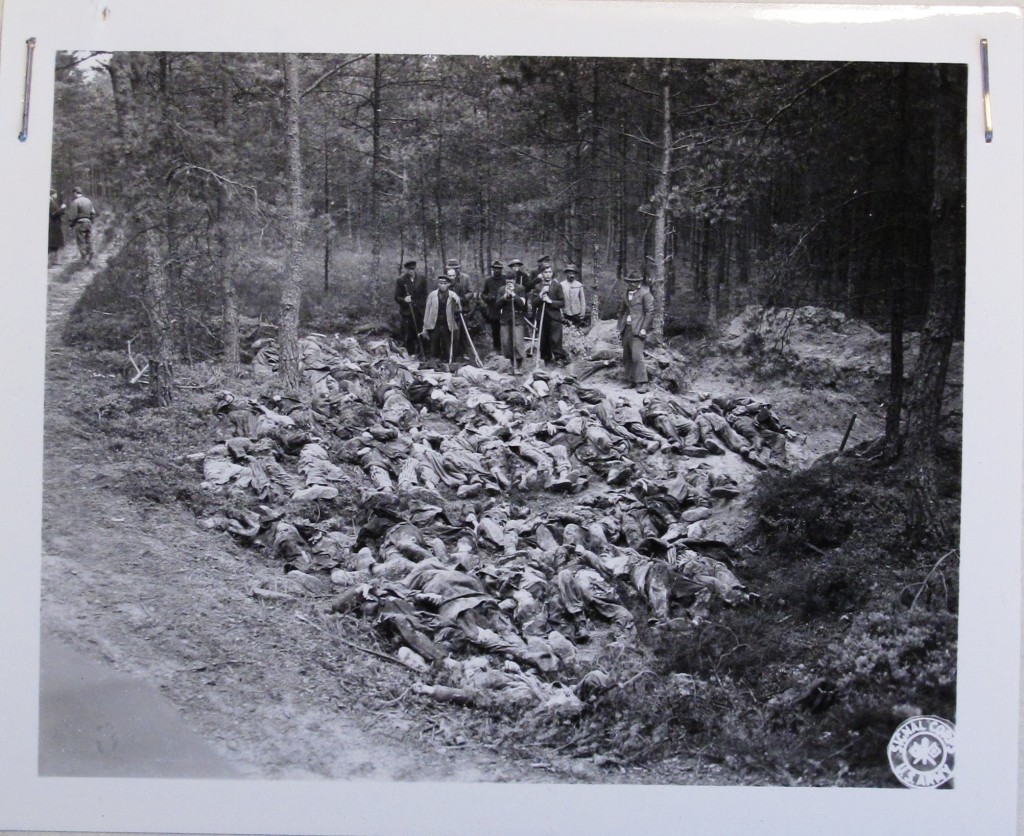

Exhumation of 49 dead in Gemeindehölzl on 1 May 1945

© NARA

This stone is to commemorate that "On this spot, on 23 April 1945, 50 prisoners were shot by members of the SS on their march from the Konzentrationlager (KZ) Flossenbürg, later exhumed and reburied in the cemetery at KZ Flossenbürg."

After a short thematic introduction about the events of the time, Mayor Franz Reichold continued, in the presence of about forty listeners, that these dead must not be forgotten and the bestial crimes must never be forgotten. And the necessary lessons from this dark history must prevent similar crimes in the future.

In what follows, the events of the time and their aftermath are described together, accompanied by reminders from which the resulting memories of these horrific events should be concluded.

The Death Marches of Flossenbürg

In early April 1945, preparations began at Flossenbürg for the liquidation of the concentration camp. First, prominent prisoners were transferred to camps further south.

Flossenbürg concentration camp

Archive

Afterwards, the first large group of Jewish prisoners was sent on April 17, 1945, on their way to Dachau. About 2,000 prisoners were initially loaded into trucks and sent by rail through the Swarzchwald Forest, but after air raids by American planes they had to continue their march on foot.

On Friday, April 20, 1945, four more large columns of prisoners left Flossenbürg on foot. Meanwhile, more transports of prisoners from Buchenwald arrived at the camp. Subsequently, and in total, some 15,000 prisoners were expelled from the camp towards the south, with hundreds of sick people still remaining in the camp.

The columns of prisoners marched mostly at night and divided into even smaller groups. They partly intermingled, preceded and joined, which does not even allow any detailed reconstruction of their movements.

As provisions, the prisoners in KZ Flossenbürg were given a handful of grain and some bread. If they managed along the way, they were mostly given potatoes, which the SS march leaders requisitioned from local farmers.

Surviving prisoners described constant life-threatening malnutrition and, above all, a constant lack of clean drinking water and terrible thirst.

The prisoners had to spend the night mostly in barns, partly outside. They were guarded by members of the SS and German prisoners who had also been imprisoned in Flossenbürg for criminal acts, but they were deliberately dressed in SS uniforms and partly armed for the evacuation marches.

The SS escorts' luggage was loaded on carts that the prisoners had to pull. Those who could not keep up with the set marching pace and could not or would not go on were shot or beaten.

Because the SS officers did not want to fall into captivity of the advancing American army, they increased the marching pace of the already exhausted prisoners, and even for this reason they executed some of them daily.

Nazi Mayors in a System of Destruction

Initially, the dead had to be buried by prisoners from one designated group along the roads where the marches proceeded, which warned the survivors. As the number of dead increased, SS leaders ordered local mayors to bury the lying corpses of prisoners with the local population.

As the mayor of the village of Rötzer, Jakob Stichaner, later testified, he was ordered by an SS lieutenant "before dawn to prepare the village plot and gather the killed prisoners" and bury them.

Thus, at the urging of Rötzer Mayor Jakob Stichaner, more than 140 of the dead were buried in a mass grave by local civilians.

Anyone can guess what crimes the advancing American army was uncovering. Data collection in the trials of the prisoners' killers continued until 1959, with Mayor Jakob Stichaner acting as a witness during the trials.

He did not, however, recall the names and likenesses of the SS leaders responsible. And Mayor Stichaner was not sure of the names presented to him.

Nazi mayors like Jakob Stichaner acted mostly as accomplices of the SS under the Nazi government. They covered up crimes during the death marches for 14 years after liberation. After the collapse of the Nazi establishment, mayors (often members of the NSDAP) could not be expected to be active in exposing crimes and their perpetrators.

The horrific image of the roads and the fear of reprisals

The misery and death of prisoners during the death marches was certainly directly visible to thousands of civilians in countless places. The reaction of civilians was limited to dismay and little willingness to help, which appeared, especially in local narratives, uncertainly. Mostly it was indifference, ridicule and hatred towards the prisoners. Rather, it was a general dislike of the imprisoned and harmful enemies of the nation and a similar mindset.

This was the judgment of an ordinary surviving prisoner in recalling the rejectionist attitudes of the civilians at Stamsrieder. There, prisoners who walked past Hansenried and Diebensried during the day had to spend the night of April 22, 1945, in local barns with peasants.

This was also the case in "Hoffner-Stadl". SS leaders, on the other hand, were allowed to spend the night in houses around the roads. The next day, on Sunday morning, the children found many dead bodies according to the roads where the prisoners had lain down the night before.

As in Rötz, those murdered in the Stamsrieder area were loaded onto carts during the days, certainly also on the orders of the SS column commanders. Under the direction of Nazi mayor Alois Preißer, the civilians then buried the dead in three mass graves on the roadsides.

In his 1961 memoirs, Alois Preißer described the situation on the day before the liberation, "It was only necessary to quickly remove the terrible picture on the road with the many prisoners killed, because it was feared that this situation might perhaps lead to a large-scale reprisal."

Like most other mayors, Alois Preißer was not involved in any Christian funerals or even in the identification of the dead victims.

Massacre on the morning of 23 April 1945

On April 22, 1945, the first prisoners arrived at Wetterfeld via Pösing. There they met a resident who went directly to the church for the service. There was also one column housed in a farmer's barn and poorly provided for. Probably the evening before that day, the decision was made to kill those prisoners who, according to the SS command, could not endure the ordered pace.

In preparation for the execution, the men from Wetterfeld and the prisoners of war who had also been deployed in Bavaria for forced labor had to go to Gemeindehölzl, about one kilometer away, and by dawn on Sunday, April 23, 1945, manually use spades and shovels to deepen and enlarge the original small hole in the sand there.

Quite probably, this plan, based on the decision of the SS commanders leading the column, was presented to Nazi Mayor Josef Groitl (died 1954) and orders were given to him to do so. As local accounts testify, part of the task was also assigned to forced laborers.

Several hours before the American armored division arrived in Wetterfeld, about 50 prisoners had to leave their night camp in Wetterfeld. The guards herded them toward the Gemeindehölzl.

Unable to move, the prisoners were loaded onto a horse-drawn wagon driven by the 15-year-old son of an NSDAP member, some in Wetterfeld recalled. At the prepared pit, all the selected prisoners were shot or killed without mercy.

After this massacre, the dead were buried, probably by the same persons present who had dug the pit at this place. However, there is no information on this. These people designated to do so have remained silent about it for a long time.

Two prisoners very badly injured, however, survived and were rescued from the pit - but they were unable to identify anyone from the village. By noon, American soldiers reached Wetterfeld, where they were still being attacked by the fortified German fanatics.

Liberation of Wetterfeld

About 3,000 to 4,000 prisoners, and among them Jews, were liberated between Stamsried and Cham on April 23, 1945 by American soldiers from the 11th Armored Division. Shortly thereafter, the greatest suffering of their lives was ended for the last few prisoners in the adjacent Thierlstein.

Among the others to arrive at Wetterfeld was Joe Hecht, then 18 years old. The considerably weakened Joe, the son of an Orthodox Jew from Romania, was transported in January 1945 from Oswiecim to KZ Flossenbürg.

From there he was transported with other Jewish prisoners as early as 17 April 1945 in a cattle truck to Schwarzenfeld, where American air raids stopped the train. He then continued on foot to Wetterfeld.

Only liberated prisoners like him could recall any local details. So Joe assured in his interview how, in the pervasive wet and cold and feeling of a life without purpose, he had to walk across the countryside with a constant life-threatening lack of food and drink.

On the 70th anniversary of his liberation, Joe Hecht arrived from New York with his wife, Blanche, at the site of his liberation, looking for the barn from which the U.S. military had liberated him, completely starved, on April 23, 1945. For him, the death march would always be hell on earth, and the Germans, he thought, were all Nazis.

Only a few marching columns reached their destination at KT Dachau. For some 5,400 evacuated prisoners, liberation from the US Army came too late. They were beaten, shot or buried alive by the Germans. And not a few died of sheer exhaustion. Because of these high casualties, the Americans began to call the marches "Death Marches" and hence the renaming of these marches in German to "Todesmarsches", the death marches.

Which of the American troops at Wetterfeld on the Gemeindehölzl discovered the buried corpses is not precisely documented. Therefore, even the memorial stone does not describe anything about the further fate of the prisoners killed here, and therefore Robert Werner's brief research ends here.

Exhumation and Conciliation Burial by Order of the U.S. Army

From photographs in the U.S. National Archives (NARA), it is more likely that the mass grave at Gemeindehölzl was not discovered until May 1, 1945.

According to other reports on the consecration of the stone memorial at Wetterfeld near Roding, the dead there were not exhumed before mid-June 1945.

One of the U.S. Army Documentation Corps photographs shows about 18 men, 13 of them with shovels, rakes, and brooms, who had to dig up the buried victims under the supervision of U.S. Army soldiers and in the presence of the commander.

Exhumation group with Mayor Josef Groitl in Gemeindehölzel on 1 May 1945

© NARA

After the first exhumation of the photographed dead, at least 10 of Weterfeld's victims could be identified. In the center, with a bandage on his arm, poses Josef Groitl, the mayor who was not yet deposed at this time. Those who buried the dead eight days earlier are probably also in this photograph.

In the first photo, a U.S. Army cameraman can be seen. A series of these photographs were used as evidence in the Flossenbürg trial, which followed the Dachau trial (from 1945 to 1947).

While the defunct SS and other commanders were partially sentenced to heavy sentences, the execution at Wetterfeld was not completed. Some court hearings did not return to this until early 1960, but the proceedings were dismissed for lack of evidence.

The U.S. Army photographs show sites that are no longer safely identifiable today. According to details in one of the photos, 49 dead bodies can be seen lying loose and carelessly to the right of a westbound forest road, about 25 yards from its start.

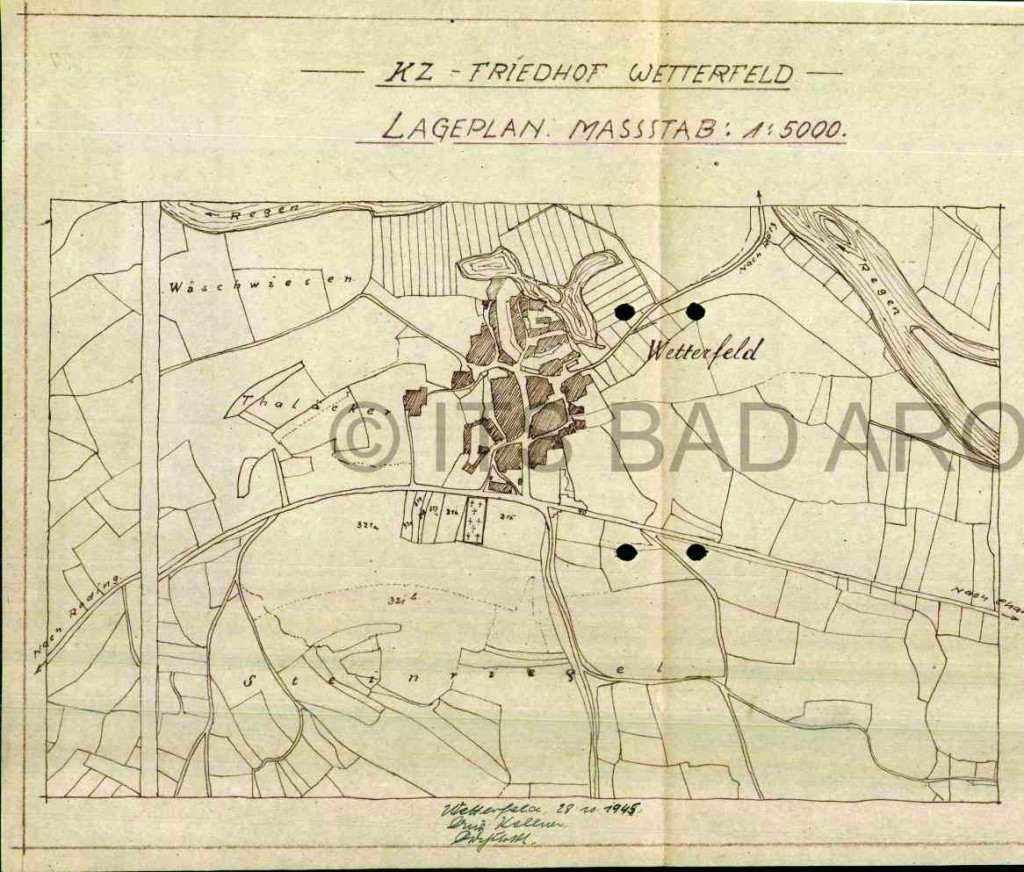

After the victims were exhumed, their bodies were taken back to Wetterfeld by order of U.S. Army commanders, deposited there on the village green, transferred to stretchers, and reburied soon after. According to a report filed with a Belgian authority, on 6 May 1945 a total of 52 dead were buried right on the edge of Federal Road 85. This happened at the so-called Busl-Feld site, which had been requisitioned for this purpose and marked as a cemetery by decision of the U.S. Army command. The original map of Wetterfeld shows the site of the execution of the 50 prisoners and their transfer to the newly established cemetery off State Route 85 [3]

Wetterfeld Cemetery with 52 graves at the end of October 1945

As in similar cases of these burial ceremonies - as in Schwarzenfeld or Neunburg vorn Wald - the Weterfeld villagers had to pay their last respects and blessings to the dead. The Rodinger painter Ludwig sketched this situation, which was also filmed by American filmmakers (the drawing and film are in the NARA [2] archives).

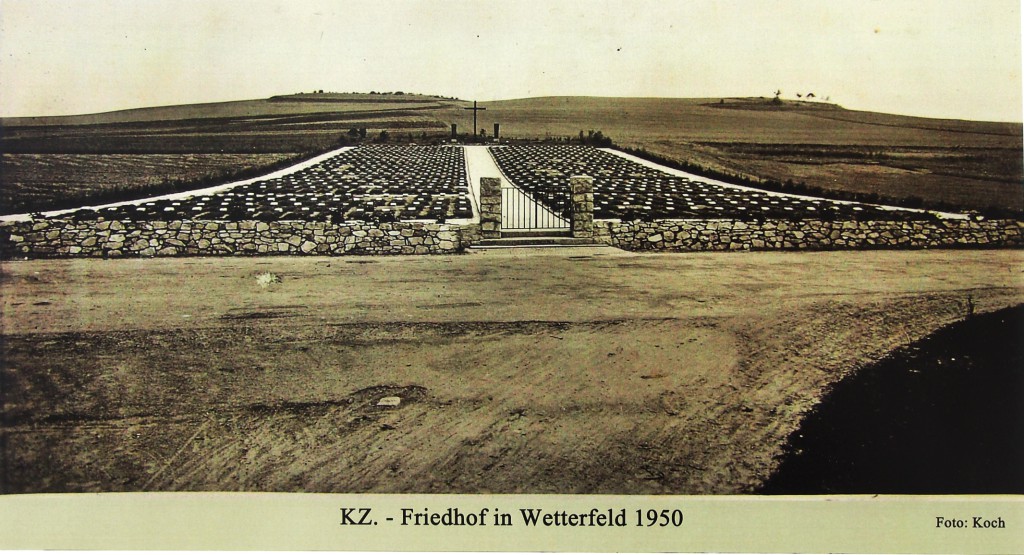

Cemetery of the Wetterfeld concentration camp 1950

Photo from the Dieß 2015 exhibition

The 52 graves were just the beginning. Over 500 other casual burial sites of slain prisoners were traced around the roads and paths around Pösing later that year.

The Wetterfeld Cemetery

Since the early summer of 1945 there had been suggestions that the murdered prisoners in the region around Roding should be exhumed and, if possible, identified. Under the leadership of the newly formed military unit, Captain Charles R. Buchheith set October 1945 as the beginning of the action and appointed a committee of six Polish doctors, on whose part there was to be a clear interest in the identification and reinterment of the murdered prisoners.

"From the earlier cross at Stamsried" came the initiative to "in the bestial conditions of murder... and buried prisoners to have one correspondingly quiet place in Wetterfeld to rest", reads the final report of 3 May 1946, translated into German. This report was written by the chairman of the commission, the physician Dr. Tadeusz Wolanski.

The report also includes an examination of the manner of death. To do this, 597 dead had to be exhumed, of whom 364 were shot, 44 beaten and 32 suffocated. For 19 of the dead, the cause of death was given as general debility and for 138 the exact cause of death could not be determined.

The autopsies of the dead and their transfer to the Wetterfeld Memorial Cemetery, for the preparation and finishing of which NSDAP members from the entire surrounding region were assigned as workers, were completed in November 1945. Thus was created a large memorial cemetery in Bavaria of about 3000 m2, complete with 600 small wooden crosses with numbers.

Wetterfeld with concentration camp cemetery circa 1955

Busl

The specific identification of the dead evacuated prisoners, made by the numbers on their clothing, was difficult and protracted. It was mainly carried out under the direction of August Schrober, the caretaker of the Wetterfeld cemetery. Schrober, an Austrian survivor of the death march, was in contact with the Bavarian authorities, represented by the Association of Nazi Victims (Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes), an international search service, an offshoot of the Dachau-based International Prisoners' Association.

Because the KZ camp at Flossenbürg was overcrowded with prisoners from other camps in early 1945, it was often found that many of the prisoners had the same numbers, which made identifications very difficult. Therefore, by decision of the Pösing registry office in 1947, the identifications were discontinued and ended in 1949.

Of the 597 exhumed prisoners in the Wetterfeld cemetery, only 236 prisoners could be identified, and these were supplemented with names at their reinterment sites. One exemplary result that has not been replicated at any other prisoner burial site in the American Zone.

First, the names of the victims from the Gemeindehölzl massacre

How many dead were there in Wetterfeld? Here, by the autumn of 1945, some 60 dead were found scattered and buried throughout the area, examined and reburied.

This includes the 49 dead from Gemeindehölzl who were discovered in May 1945.

In one funeral list we can thank the work of the identification committee for the 41 names of prisoners who died at Wetterfeld, including the names of the dead from the Gemeindehölzl. Some were repeatedly exhumed and examined this autumn.

Even with an adequate forensic examination at the burial site, unfortunately many of the unidentified continue to remain with only the murder site marked "Wetterfeld".

According to the joint evaluation of identification reports and sketches drawn between 1945 and 1948, it was possible to assess the manner of death of each of the 49 prisoners killed in the massacre at Gemeindehölzel. They were certainly shot or killed.

At least 10 names of victims were identified from these identification protocols, including four Jews from Poland and Hungary, one Dutchman, one German and four Poles.

An example for the other victims can be found in the case of the Hungarian Jew Istvan Löwy (dated 24 December 1919), who was briefly imprisoned in the KZ-Außenlager Colosseum in Regensburg. His murderer shot him in the face: 'Gunshot between the eyes, both jaws and palate torn'. This is written in the protocol and signed by Dr. T. Wolanski on October 24, 1945 in Stamsried.

Annual celebrations, official consecration and final resolution of the burial grounds

On 1 November 1946, the Wetterfeld cemetery came under Bavarian administration. On this occasion, a commemorative meeting was held at the cemetery, attended by delegations from France, Belgium and representatives of the U.S. occupation administration.

An envoy of the designated Bavarian State Commissariat "Victims of Fascism" thanked all the organizers for the construction of the cemetery and for their participation, and the Jews sang one funeral song.

On the second anniversary of the end of the war in Wetterfeld, among others, the head of the exhumation team, Dr. Tadeuz Wolanski, spoke - he thanked the 3. U.S. Army for its liberation of thousands of prisoners two years ago.

Bavarian State Commissioner for Racial, Religious and Political Victims of Nazism, Filip Auerbach, assured that the survivors "never want hatred, revenge and retaliation, but demand proper condemnation in the name of divine and human rights from everyone to whom the blood of the dead clings" (MZ at 25 April 1947). And just as they condemn current anti-Semitic sentiments.

The warnings uttered by Philipp Auerbach about the possibility of a return of anti-Semitism, which were widespread in Germany thanks to the Nazi regime, were partly due to the German population's fear of possible Jewish revenge and brought tension to Stamsried and Wetterfeld, as depicted in the Acts.

During the five years after the end of the Nazi regime, Filip Auerbach visited Wetterfeld twice more. This time already as head of the Bavarian Office for Land Compensation (Landesent-schädigungsamtes) the last time on 4 November 1950 shortly before his appointment to the management of the Administration of Memorial Cemeteries. The celebration was organized by the Christian denominations and the provincial rabbinical organization.

This state-led celebration had a great local and political impact, to which the council of the nearby town of Roding and the incoming mayor and municipal council contributed with personal presence and written invitations.

After the scheming removal of Philip Auerbach's office in 1951, post-war memorial cemeteries came under the Bavarian State Administration of Castles, Gardens and Lakes, and this led the Bavarian Ministry of Local Government to plan the final solution for many post-war burial grounds.

One decision by the French authorities, who also had and kept their buried dead in Germany, was followed by one for the Wetterfeld cemetery. Due to the German-French reconciliation of 23 October 1954, the French search for war victims was terminated and it was decided to exhume and relocate all the dead in Wetterfeld.

This occurred in 1957 from early to mid-June - the protocol of 19 September 1957 lists only 566 exhumed dead. The buried remains of prisoners of French, Belgian and Dutch nationality were transported to their home countries, the remaining bones were placed in coffins and later reburied in the new cemetery in KZ Flossenbürg.

Wetterfeld 2015: the B 85 extension runs through an abandoned concentration camp cemetery

Werner

Before this definitive act, the Wetterfeld burial ground was still used for several months as a collection and washing station for other excavated corpses from other Bavarian burial grounds. After the sorting of the dead by place of birth was rejected by the municipal council, the local employees assigned to this exhumation and listed as "bone cleaners" were also rewarded.

Although it was agreed in the aforementioned state contract that the Wetterfeld burial ground would be replaced with a cross and two information panels on the original site and permanently secured as a memorial, this was not adhered to. Today, Federal Route 85 runs through the site and has been extended into the original cemetery area.

Constructing and Relocating Memorials

Soon after the approval of the destruction of the burial grounds and their conversion into mere memorials, the Wetterfeld municipal council sought to purchase the fallow remnant of the burial ground from the Bavarian state. According to a letter dated 24 January 1958, it was assumed that the memorial would be relocated and a school gymnasium and playground would be built in its place.

Current memorial - on the hill since 1973

Werner

After further discussions and proposals to remake that municipal burial ground into something, the management of Bavarian Castles, Gardens and Lakes agreed to sell it. But at the same time, they set the following conditions: first of all, there must be an information board by the road on the way to the new site, and then another information board by the road with the text that the dead are moved from here to Flossenbürg. This was written in a statement dated 7 April 1960. And that neither a sports ground nor a municipal cemetery would be established on this former burial site.

The last attempt of the local population for the use of the area of the former burial ground was therefore rejected. The ordered plaque about the transfer of the dead to Flossenbürg was only installed in 1962 with three more plaques.

Some years after that, Wetterfeld was annexed to Roding in 1972 and the cross and the three wooden plaques, which had already fallen into considerable disrepair, were again relocated to a nearby wooded eminence - eventually the Wetterfeld settlement built in 1970. The dilapidated wooden boards were therefore restored.

Disappearing memorials without names?

The little information given here is rather confusing. On the left plaque, interested Christians can read:

"600 KZ prisoners of many nationalities rest here as victims of the SS - they live in Christ."

The middle board comments incorrectly on this anachronistic sentence content. Here it is stated deceptively:

"The 567 KZ prisoners previously buried here were moved to the Flossenbürg Memorial Cemetery in 1957".

But the graves were not here, but under the federal road. Moreover, the different numbers given - 600 prisoners once and 567 the second time - are quite unintelligible. On the right-hand board it is written rather cryptically:

"In the regional district of Roding during the death march from Flossenbürg to Wetterfeld in April 1945."

This is what the current memorial looks like since 1973 in the town of Roding on a high ground near the Wetterfeld district in a photo by Robert Werner.

So there is a four-part memorial in Wetterfeld, which remains incomprehensible with conflicting numbers and texts displayed. One inconclusive memorial that is not even on the original site and is only associated with one lost post-war cemetery with local significance without any thematic explanation.

In any case, what is missing from the Wetterfeld memorial is any reference to the fact that the actual cemetery lay about 400 metres to the north on the federal road.

If the town of Roding wanted to make historical events easier for its visitors and residents to understand, it would offer them a more appropriate information board, such as the one that was set up, for example, at the original cemetery at Neunburg von Wald.

Here, the history of the death marches from the Flossenbürg concentration camp and the history of the original cemetery are briefly, adequately and comprehensibly explained. The text there is written by collaborators of the Bavarian Memorials Foundation, which since 2013 has also been responsible for the memorial in Wetterfeld.

Many years have passed since the first memorials were set up in early September 1945 for those murdered at Gemeindehölzl and later expanded to memorial cemeteries, which, although also without precise markings and often with confusing or unclear information, did not explain the murderous events but rather relativized them. It has been suffered and is still perceived today that the town of Roding wants to erase the death marches and their aftermath from its historical memory.

Surely some serious commemoration can fail without processing and knowledge of historical events. If the city of Roding is concerned with an appropriate remembrance of the victims of the death marches, at least the naming of the fate of the murdered prisoners in Roding and Wetterfeld should not be neglected.

The road to a comprehensive understanding of Nazi crimes and the support and suffering of Nazi society has not yet been completed in Germany.

From the original article by Robert Werner [1] translated and abridged for the website www.valka.cz

Pavel Oupicky

14.8.2019

Literature used:

[1]Die namenlosen Toten von Wetterfeld

[2] www.archives.gov (NARA)

[3] arolsen-archives.org (ITS Bad Arolsen)

[4] www.gedenkstaette-flossenbuerg.de

[5] Wetterfeld, concentration camp cemetery

[6] KZ Flossenbürg

[7] www.vets.cz

Translator's note:

I did not translate this article by Robert Werner by mere coincidence. Since the winter of this year I have been searching for the fate of radio amateur Pavel Homola OK1RO, a teacher and friend of my father-in-law Ivan Šolc OK1SI.

About Pavel Homol it was known only that he died during the transport from Terezín and nothing more. In the course of this search, I received a report from the National Archives of the Czech Republic about a document from the archival fund of the Occupation Prisoner Files that Pavel Homola was buried on April 23, 1945, by US Army troops near Pösing, the place where the US Army actually liberated some of the prisoners "evacuated" from the Flossenbürg concentration camp and almost on the same day other troops also liberated this camp, and the date of April 23, 1945 is usually written there.

And in the course of this research around this camp and these death marches, I also found an article by Robert Werner that seems to faithfully describe the events surrounding these marches and also the sites around the fateful place for Pavel Homola. And that was the reason why I took the trouble to translate this article and why I asked Robert Werner for his permission to translate it and to refer to his article and photographs (these are given in the unabridged version of the translation) and I thank him once again for his permission and for his article in the original German.

Pavel Oupicky

Malá Skála, 18.8.2019

Join us

We believe that there are people with different interests and experiences who could contribute their knowledge and ideas. If you love military history and have experience in historical research, writing articles, editing text, moderating, creating images, graphics or videos, or simply have a desire to contribute to our unique system, you can join us and help us create content that will be interesting and beneficial to other readers.

Find out more